I have friends who have been in Christmas movies, who have directed Christmas movies, and who have produced Christmas movies, but I’m not sure I’ve ever thought about Christmas movies as a genre before this year.

It’s not that I’ve never seen a Christmas movie. I’ve seen Miracle on 34th Street. I’ve seen Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. I’ve seen A Christmas Story multiple times. I will happily rhapsodize about It’s a Wonderful Life, which truly is a wonderful picture, or warmly recall my childhood’s annual viewings of the Albert Finney Scrooge. And if someone wanted to argue that Die Hard or Gremlins or Batman Returns was a Christmas movie, I could happily assent, because I didn’t have any particular view on the question of how such a genre might be defined.

Well, this year I finally saw my first, proper, Hallmark-style Christmas movie, the kind of thing that John Podhoretz makes affectionate fun of every year. And I think I may now have some actual thoughts as to what the genre is all about.

The film is Single All the Way. The premise of the film is that perpetually-single Peter (Michael Urie) is obviously supposed to be coupled with his roommate, Nick (Philemon Chambers), but they are “just friends,” and it will take some time home with (and some mild conniving by) Peter’s family, combined with a little bit of courage on both Peter and Nick’s parts, to finally bring them together—during a Christmas visit to New Hampshire where Peter’s family resides. There’s no real conflict of any kind, no tension, no surprise, and definitely no villain. Everyone loves each other, all the humor is warm and friendly, and it’s obvious from the first ten minutes that the romance at the heart of the film will come together exactly as it should. And the key to that romance coming together is simply that both men (Peter in particular) need to open their hearts, and to speak what they find there. Based on this one example, I have concluded that the single overarching requirement of the Christmas movie is gentleness.

It’s an easy sort of thing to mock, and I’m not going to pretend I loved the film. But it’s actually harder than it looks to make a film like this without cheating. So I’ll give the writer, director and cast of this film real credit for that fact: it doesn’t really cheat. By that I mean that there wasn’t anything that took me out and said: that’s false to this world or to that character, and was just put in there to make the story come out the way the Christmas movie gods demand. This is a low-stakes world where everything is dialed down to 3 rather than up to 11, but it’s plausibly low-stakes. Everyone is nice, but everyone is nice in a way that people can be nice. Even the hunky guy that Peter is set up with, who leans the furthest in the direction of existing only to deliver lines that Peter needs to hear, stays just real enough that he seems like a plausible nice, perceptive guy rather than a clunky device. I mean, he is a device—but not a clunky one, and I think that deserves recognition. When a story is this obvious and formulaic, it takes skill to make it feel like a world.

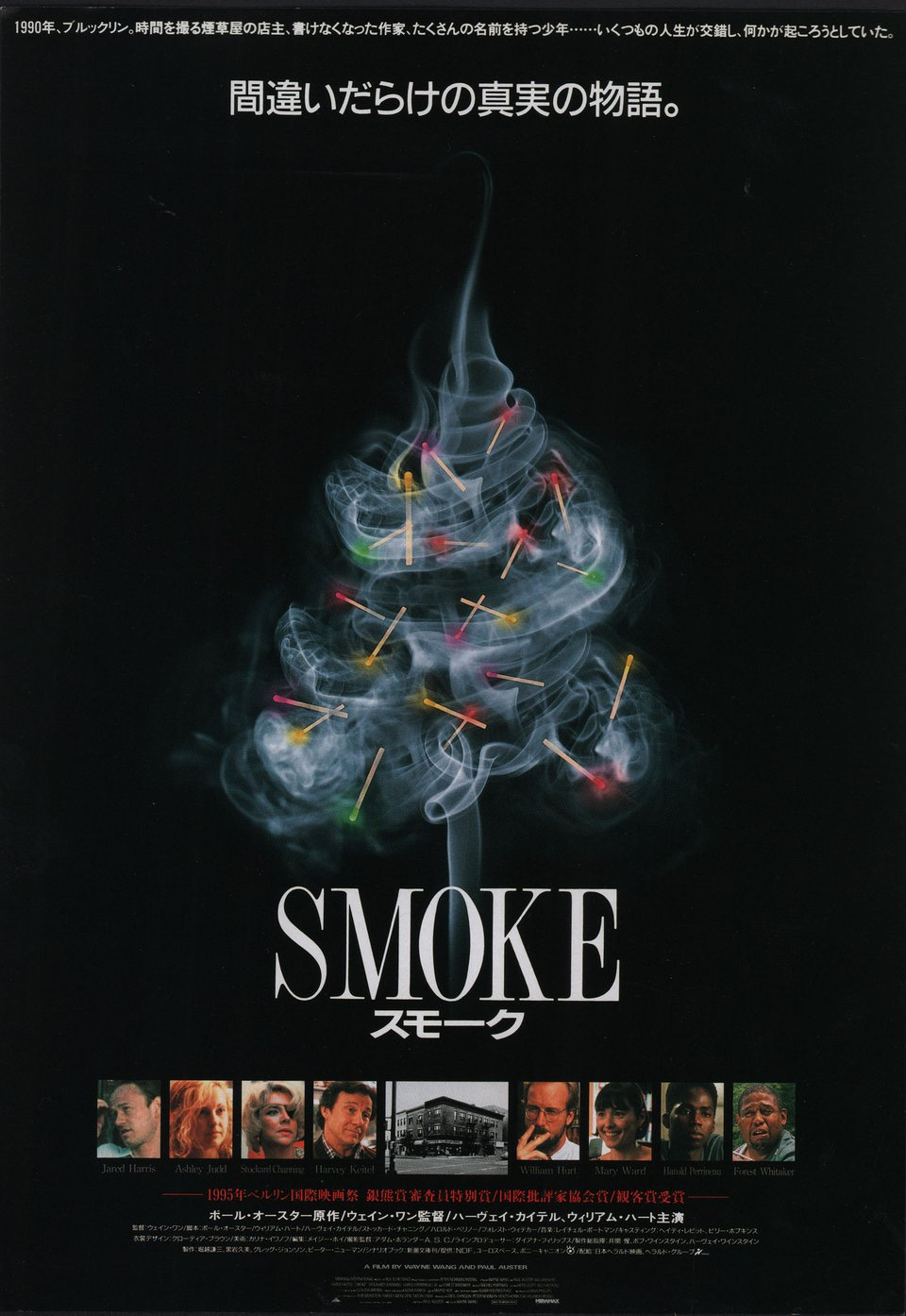

I certainly won’t dissuade you from watching Single All the Way if you like Hallmark-style Christmas movies. The film I’m actually going to recommend, though, isn’t one I’ve seen on any Christmas movie lists. But it clearly should be on them. Indeed, upon reflection, it’s obviously a Christmas movie and, moreover, is self-aware about that fact, as the final segment of the film involves the main character telling a made-up Christmas story that he presents as real, and by so doing implicitly tips the audience off to the nature of the rest of the film we’d just seen.

That film is Smoke, Wayne Wang’s indie drama starring Harvey Keitel, William Hurt, Harold Perrineau, Forest Whittaker and Stockard Channing. The film centers on a cigar store in Brooklyn (about a mile from where I live, I think), of which Auggie (Keitel) is the owner. The store, and Auggie, are the nexus through which a number of other neighborhood stories connect: about a Paul (Hurt), a grieving widower novelist trying to recover to life and to the ability to write; about Rashid (Perrineau), a young man who is both on the run from danger and on a quest for his father; about Cyrus (Whittaker), the object of Rashid’s quest who is trying to live as a better man than he was when he abandoned his son; and about Ruby (Channing), Auggie’s one-eyed ex-lover who barrels into town hoping to enlist Auggie in an effort to save her daughter, who she claims is also his.

That sounds like a lot of incident, and potentially a lot of conflict, but it doesn’t play that way. Nearly all of the action properly construed happens off-screen or in the past. For all the pain that is present in multiple characters’ lives, their fundamental orientation toward each other is generous and gentle. Even when they have real grievances against each other, there’s a manifest desire—particularly on Auggie’s part—to find a way past them. The only important exception to this rule is the behavior of Ruby’s daughter, in the only scene that, to me, felt like it had wandered in from a different movie, but this may be a necessary exception, since folding her within the general mood of gentleness and good will would have played false. So if her scene still lands somewhat off, at least it doesn’t undermine the whole film in the process.

The film appears to be a meandering series of stories whose interconnection is a literary conceit. But in fact, it’s a very carefully constructed story whose characters are themselves alive to the themes that animate the story they are in—which is the point, I think, of the last “chapter” of the film, in which Auggie tells Paul a Christmas story, and thereby helps us realize that we, the audience, have been watching a Christmas story all along, something carefully curated to help us believe in the power of kindness. The best example I can use to illustrate what I mean is the way gift-giving is used not only thematically but to drive the plot—how one character after another recognizes the importance of gifts they have been given, and uses that recognition as a spur to give gifts of their own (sometimes the same gift to a new person). It’s about as clear a Christmas theme as can be imagined, and even once it became obvious to me what was going on, it still worked. I felt appreciative of the artistry in the construction of the story, rather than manipulated by it, and continued to believe.

And that, I think, is the real hallmark of a good Christmas story.